Overview

- Clin Chest Med. 2011 Dec;32(4):605-44.

- Canadian Cancer Society: Canadian Cancer Statistics 2012

- Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in Canada and worldwide (about 27% of cancer deaths in Canada).

- Overall incidence of lung cancer is:

- Higher in men than women

- Declining for men since 1980s

- Declining for women since mid-2000s (reversal of increasing trend since 1980s)

- Second highest cancer incidence in both sexes after prostate (males) and breast (females) cancers.

- Lung cancer has a poor prognosis, which means incidence closely matches mortality. The five-year relative survival rate of lung cancer is 16% in Canada.

- Small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC, 15% of all lung cancer) and non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC, 85%) are the two major forms of lung cancer. Non-small-cell lung cancer is further classified into squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma.

- Smoking is the single most important risk factor for lung cancer, which can cause all types of lung cancer but is more strongly linked with SCLC and squamous-cell carcinoma.

Etiology

- Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2011 Oct;20(4):605-18.

- Clin Chest Med. 2011 Dec;32(4):605-44.

- Biochem Pharmacol. 2011 Oct 15;82(8):1015-21.

Cigarette smoking

- Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of lung cancer, accounting for about 85% of lung cancers. Risk for lung cancer increases with the duration, intensity and depth of smoke inhalation.

- Second-hand (passive) smoking also causes lung cancer, but is less strongly associated compared to active smoking.

- Cigarettes contain multiple carcinogens (more than 60) that have been shown to induce cancers in laboratory settings.

J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004 Jan 21;96(2):99-106.- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) such as benzo[α]pyrene produce mutations in the p53 gene. G to T transversion within the p53 gene is a molecular signature of lung tumours caused by tobacco mutagens.

- N-nitroso compounds are a major group of chemicals found in tobacco smoke, several of which are potent animal carcinogens.

- Nicotine: causes addiction to cigarette smoking and is also a promoter for carcinogenesis.

- Sympathetic/parasympathetic activation: nicotine binds to and activates nicotinic cholinergic receptors, which are located on both sympathetic and parasympathetic postganglionic neurons. The endogenous ligand for this receptor is acetylcholine (nicotine is not naturally found in humans). Therefore, smoking stimulates both sympathetic (increased heart rate, blood pressure) and parasympathetic (intestinal motility, relaxation) systems, releasing a whole range of hormones and neurotransmitters into the circulation.

- Addiction: nicotine causes dopamine release from the nucleus accumbens, mediating reward and addiction

- Carcinogen: nicotine does not initiate carcinogenesis, but it does promote initiated cells by nicotinic cholinergic receptor signalling in the lungs. Nicotine has been shown to inhibit apoptosis, proliferate cells, and cause angiogenesis in lung tumours.

- Distribution of carcinogens: Cigar and pipe tobacco smoking produces relatively large particles that only reach the upper airways, unlike cigarette smoking, which produces fine particles that reaches the distal airways. Thus, cancer risk is lower with cigar and pipe smoking. The addition of anti-irritants (e.g. menthol) to cigarettes allows deeper inhalation and a more rapid rise in serum nicotine levels, increasing the addictiveness of cigarettes.

- Smoking cessation: smokers at all ages can benefit from the cessation of smoking; however, the risk still remains elevated compared to never smokers.

Never smokers

- Defined as people who smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

- Accounts for 25% of lung cancers worldwide and is seen as a distinct lung cancer type.

- Associated with: female cases, East Asian populations, family history, adenocarcinoma type, EGFR mutations, and better prognosis (23% 5-year survival vs 16% for smokers).

Environmental exposure

- A number of environmental risk factors have been identified, most of which relates to occupational exposures such as asbestos, tar, soot, and a number of metals such as arsenic, chromium, and nickel.

- Air pollution has also been linked to increased risk of lung cancer.

- Indoor radon-222, a radioactive gas that percolates up soil and becomes concentrated inside buildings, have been posed as a significant risk factor for lung cancer.

Health Phys. 2004 Jul;87(1):68-74. - Smoking potentiates the effect of a number of occupational lung carcinogens (e.g. asbestos), such that risk is multiplicative instead of additive.

Genetics

- There is an increased risk of lung cancer among first-degree relatives, indicating a genetic susceptibility.

- Candidate gene studies have identified several enzymes in the cytochrome P-450 system as risk factors for lung cancer. One such gene is CYP1A1, which codes for aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase. Certain alleles of CYP1A1 are thought to increase the risk of lung cancer through increased metabolic activation of procarcinogens derived from cigarette smoke.

Precursor lesions

- Precursor lesions are of increasing interest due to implication in lung cancer screening.

- Currently there are 3 types of recognized precursor lesions:

- Squamous dysplasia and carcinoma: precursor lesion for squamous-cell carcinoma.

- Adenomatous hyperplasia: precursor lesion for bronchioalveolar carcinoma, a form of adenocarcinoma.

- Idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: precursor for pulmonary carcinoids.

- Precursor lesion for SCLC is unknown.

Pathogenesis

- N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 25;359(13):1367-80.

- Clin Chest Med. 2011 Dec;32(4):703-40.

- Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005 Sep;33(3):216-23.

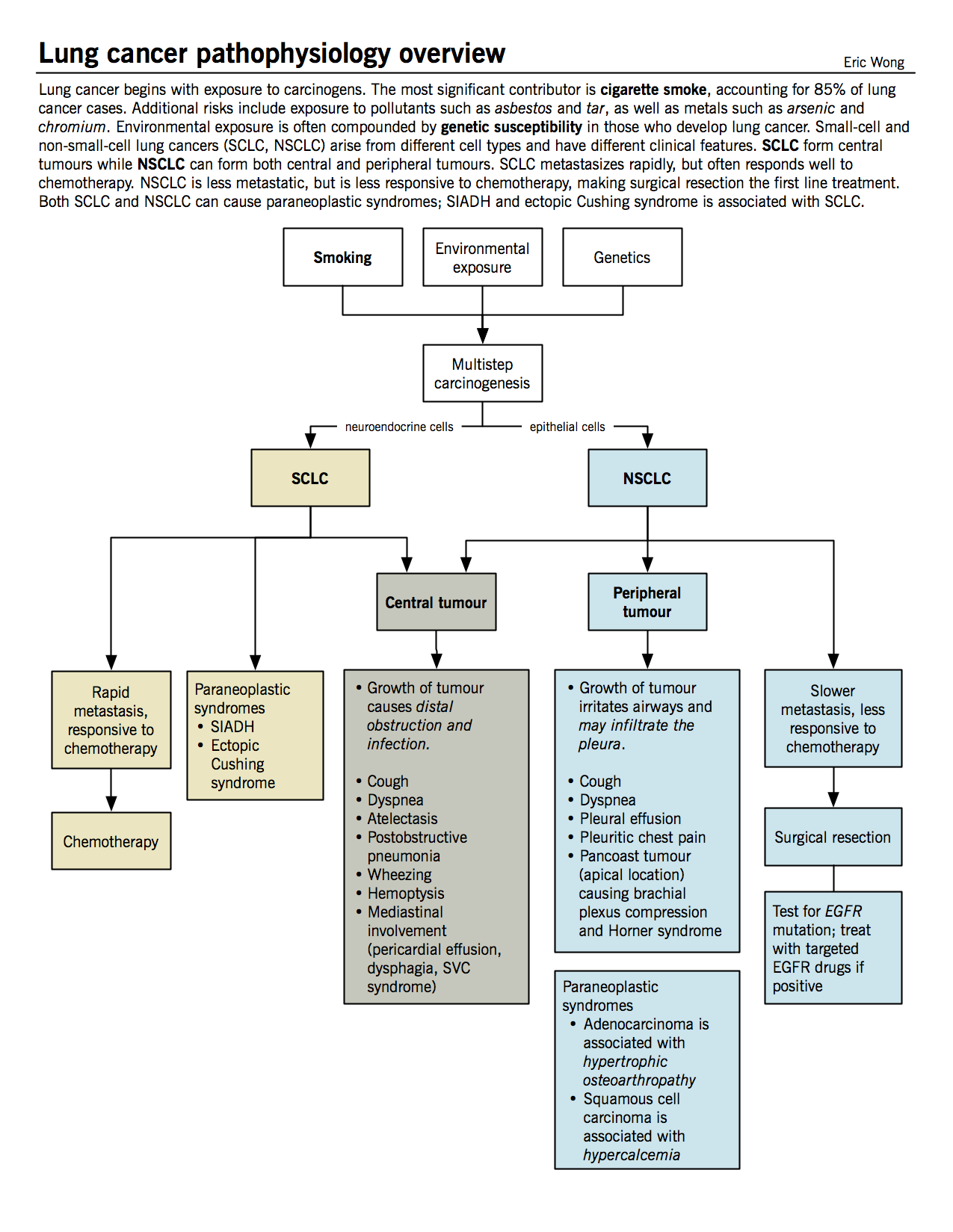

The pathogenesis of lung cancer is like other cancers, beginning with carcinogen-induced initiation events, followed by a long period of promotion and progression in a multistep process. Cigarette smoke both initiates and promotes carcinogenesis. The initiation event happens early on, as evidenced by similar genetic mutations between current and former smokers (e.g. 3p deletion, p53 mutations). Smoking thus causes a “field effect” on the lung epithelium, providing a large population of initiated cells and increasing the chance of transformation. Continued smoke exposure allows additional mutations to accumulate due to promotion by chronic irritation and promoters in cigarette smoke (e.g. nicotine, phenol, formaldehyde). The time delay between smoking onset and cancer onset is typically long, requiring 20-25 years for cancer formation. Cancer risk decreases after smoking cessation, but existing initiated cells may progress if another carcinogen carries on the process.

SCLC and NSCLC are treated differently because they (i) originate from different cells, (ii) undergo different pathogenesis processes, and (iii) accumulate different genetic mutations. SCLC often harbours mutations in MYC, BCL2, c-KIT, p53, and RB, while NSCLC often has mutations in EGFR, KRAS, CD44, and p16. These are all either tumour suppressor genes or oncogenes. See Cancer genetics and Cancer biology chapters for a description of how mutations like these can cause cancer.

Classification of invasive lung cancer

- Semin Roentgenol. 2011 Jul;46(3):178-86.

- Clin Chest Med. 2002 Mar;23(1):65-81, viii.

Lung cancer diagnosis is established by biopsy of tumours found on imaging (chest X-ray or CT). The pathological types are divided into SCLC and NSCLC. NSCLC is further divided into the types below:

|

Lung cancer type |

Location in the lung |

Features |

|

Adenocarcinoma (38%)

|

Peripheral |

|

|

Squamous cell carcinoma (20%) |

⅔ central ⅓ peripheral |

|

|

Small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) (14%) |

Central (endobronchial)

|

|

|

Large cell carcinoma (3-5%) |

Peripheral |

|

Pathophysiology and clinical features

- Cancer. 1985 Oct 15;56(8):2107-11.

- Chest. 2007 Sep;132(3 Suppl):149S-160S.

- Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2002 Oct;14(5):338-51.

The symptoms produced by the primary tumour depend on its location (i.e., central vs peripheral). Central tumours generally produce symptoms of cough, dyspnea, atelectasis, postobstructive pneumonia, wheezing, and hemoptysis; whereas, peripheral tumours, in addition to causing cough and dyspnea, can lead to pleural effusion and severe pain as a result of infiltration of parietal pleura and the chest wall.

|

Symptoms |

Mechanism and pathophysiology |

|

Primary lung lesion symptoms |

|

|

Cough (50-70%) |

|

|

Weight loss (46%) |

|

|

Hemoptysis (25-50%) |

|

|

Dyspnea (25%) |

|

|

Chest pain (20%) |

|

|

Mediastinal involvement |

|

|

Superior vena cava syndrome |

|

|

Pericardial effusion |

|

|

Pleural effusion

|

|

|

Dysphagia |

|

|

Pancoast tumour (superior sulcus tumour)

N Engl J Med. 1997 Nov 6;337(19):1370-6. |

|

|

Paraneoplastic syndromes: symptoms in cancer patients not attributable to tumour compression or invasion Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 Sep;85(9):838-54. |

|

|

Ectopic Cushing syndrome

|

|

|

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone production (SIADH)

|

|

|

Hypercalcemia |

|

|

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy and digital clubbing |

|

|

Distant metastasis |

|

|

Metastatic sites include brain, bone, liver and adrenal glands |

|

Treatment

Lung Cancer: the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011)

Smoking cessation

- Smoking increases the risk of pulmonary complications after surgery

- Three main interventions exist in addition to counselling and support:

- Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT): can be purchased in many forms including gum and transdermal patch; all forms increases rate of quitting by 50-70%.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD000146. - Antidepressants: bupropion and nortriptyline are as effective as NRT; other antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) are not effective.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD000031. - Nicotine receptor partial agonist: varenicline is more effective than bupropion and NRT.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Apr 18;4:CD006103.

- Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT): can be purchased in many forms including gum and transdermal patch; all forms increases rate of quitting by 50-70%.

Surgery

- Surgical resection of the tumour and some normal tissue around it.

- First line of choice for NSCLC who are medically fit to undergo surgery.

Radiation therapy

- Indicated for patients with stage I, II, III NSCLC.

- See Introduction to neoplasia for definition of TMN staging.

- In lung cancer, stages I, II, and III describe various sizes of primary tumour and lymph node involvement without distant metastasis. Any distant metastasis is automatically stage IV.

- Also used in combination with surgery for NSCLC and with chemotherapy for SCLC.

Chemotherapy

- First line of treatment for SCLC, which are often disseminated upon clinical presentation.

- Also indicated for patients with more advanced stage of NSCLC (to improve survival, disease control or for palliative care).

- First line therapy for NSCLC with EGFR mutations involves targeted therapies.

- Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR): epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulates cell proliferation by binding the EGFR and causing tyrosine kinase activation of effectors. NSCLC often harbour EGFR mutations that make the receptor more active, signalling downstream effectors to increase cell proliferation. Two classes of drugs target this particular aberrant protein: EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (erlotinib and gefitinib) and monoclonal antibody targeted at EGFR (cetuximab). Both classes of drugs are usually effective initially in tumours with EGFR mutations, but relapse often occurs due to accumulation of other mutations.

Palliative care

- Advanced disease may be present at the diagnosis. Given the poor prognosis, the goals of lung cancer therapy may be switched from curative to palliative. Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life and reduce suffering for patients rather than to prolong life.

- Studies have shown that early palliative care actually prolongs life in lung cancer patients (by 2.7 months in a study with metastatic NSCLC patients). It also reduces patient suffering, healthcare costs, unnecessary treatment, and impart greater patient and family satisfaction.

N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 19;363(8):733-42.